What is therapeutic drug monitoring?What is drug monitoring and what is its purpose?

The term therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) was used historically to refer specifically to the monitoring of drugs with a narrow therapeutic index or window, to ensure that blood levels necessary for a therapeutic effect are achieved and levels associated with adverse effects are avoided.

In this article we use a wider definition, that encompasses the more conventional TDM, where appropriate, but also the effect of the drug in the patient more generally.

Drug Monitoring Checker supports health professionals make effective drug monitoring decisions at the point of care. Write “TDM” in the further details section of the form below to find out about access.

Medicines have a vital role in maintaining health, preventing illness, and managing chronic conditions so it’s important that people get the best outcomes.

Everyone responds to drugs differently and most drugs have a range of different therapeutic effects. Health professionals need to monitor how well medicines are working in practice, to inform decisions about dose adjustment or discontinuation of treatment.

Drug monitoring may be necessary due to factors related to the drug (i.e. those with a narrow therapeutic index) or factors related to the specific patient (i.e. impaired kidney function or genetic variations). It could also be required due to a combination of both.

This article outlines the importance of drug monitoring and explores the challenges of accessing the right information when it is needed.

*See references

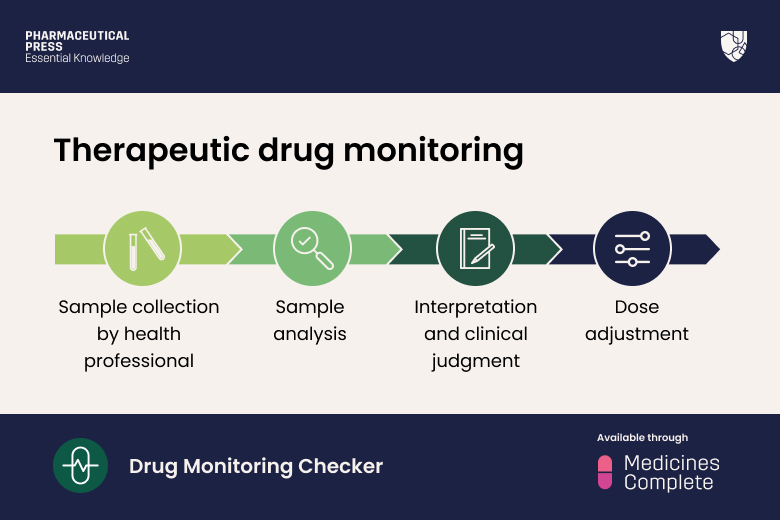

Monitoring of drug therapy can be achieved in several different ways. It can be approached subjectively, simply by asking the patient about changes in their symptoms.

For many medicines, however, it is possible to take a more objective approach, either by measuring the actual clinical effect or measuring a biomarker that acts as a surrogate for the clinical endpoint.

Some drugs require monitoring in all patients. This may be due to the potential for side effects that could outweigh the benefits of treatment if they arise. For example, aminoglycoside antibiotics, such as gentamicin, require monitoring to avoid adverse effects on the kidney (nephrotoxicity) and hearing (ototoxicity).

Other drugs may only require monitoring in certain circumstances. Various factors can all alter drug levels in patients, such as:

- pregnancy

- temporary illness, such as infection

- physical and emotional stress

- surgery.

Likewise, co-morbidities such as kidney or liver disease can influence how the body handles drugs.

Depending on the drug and the patient, monitoring may be used to:

- measure therapeutic effectiveness

- screen for and prevent adverse drug reactions

- assess medication adherence.

Tests such as blood pressure measurement, blood tests e.g. liver function, or imaging, may be conducted before or during treatment, and after treatment discontinuation. Health professionals use the results to guide decisions around dose or regimen adjustment, or treatment discontinuation.

With some medicines, clinical endpoints can be measured directly (e.g. control of heart rate in a patient taking amiodarone for arrhythmias). The dose can be titrated to achieve the desired heart rate.

For other medicines, surrogate endpoints are used to predict success or failure in achieving the desired outcome.

The surrogate end point may be directly related to the clinical endpoint, for example, serum cholesterol levels as a surrogate for risk of myocardial infarction in patients taking statins, or indirectly related to the clinical endpoint, such as serum C-reactive protein as a surrogate marker for resolution of inflammation.

The number of blood tests being carried out in primary care to monitor drugs and diseases is growing fast and likely to increase further in the coming years as patient care is moved from outpatients into the community.

There are 50 million blood tests undertaken in UK general practice each year; a recent study suggests that 40% are for monitoring purposes alone.¹ ² At the beginning of the 21st century a patient might have expected one blood test each year, yet by 2015, this number had increased to five tests each year.³

A UK-wide audit found that 25.1% of all tests ordered in primary care were deemed partially or fully unnecessary upon retrospective review by another clinician.¹

These findings align with a 2008 UK study, which estimated that 25% of primary care tests may be unnecessary.⁴

The rise and overuse of tests have led to increased NHS spending, with UK primary care spending an estimated £1.8 billion annually on laboratory tests.³

Overcome the challenges of drug monitoring

Drug monitoring is an essential part of delivering quality care. It can ensure patient safety, optimise efficacy, and confirm medication adherence.

Patients also need to be fully informed about their medicines and aware of the goals of treatment, as this can improve adherence.

Drug monitoring information

Despite the importance of drug monitoring, the process can be fraught with challenges. Finding the information needed to guide evidence-based decisions can be arduous and time consuming.

There was no single authoritative source for drug monitoring advice. Instead, health professionals have relied on a wide range of resources, including manufacturer’s information and national guidelines.

Drug Monitoring Checker, available through MedicinesComplete, provides fast access to accurate and independent drug monitoring information at the point of need.

Three critical challenges with drug monitoring

Primary and secondary care health professionals face three critical challenges when it comes to drug monitoring in practice.

1.

Finding the right drug monitoring information in a timely way when it is needed. In recent years, clinical workloads have grown in both volume and complexity. Teams are caring for an increasing number of patients with multiple co-morbidities on complex medication regimens and there are many competing demands on their time.

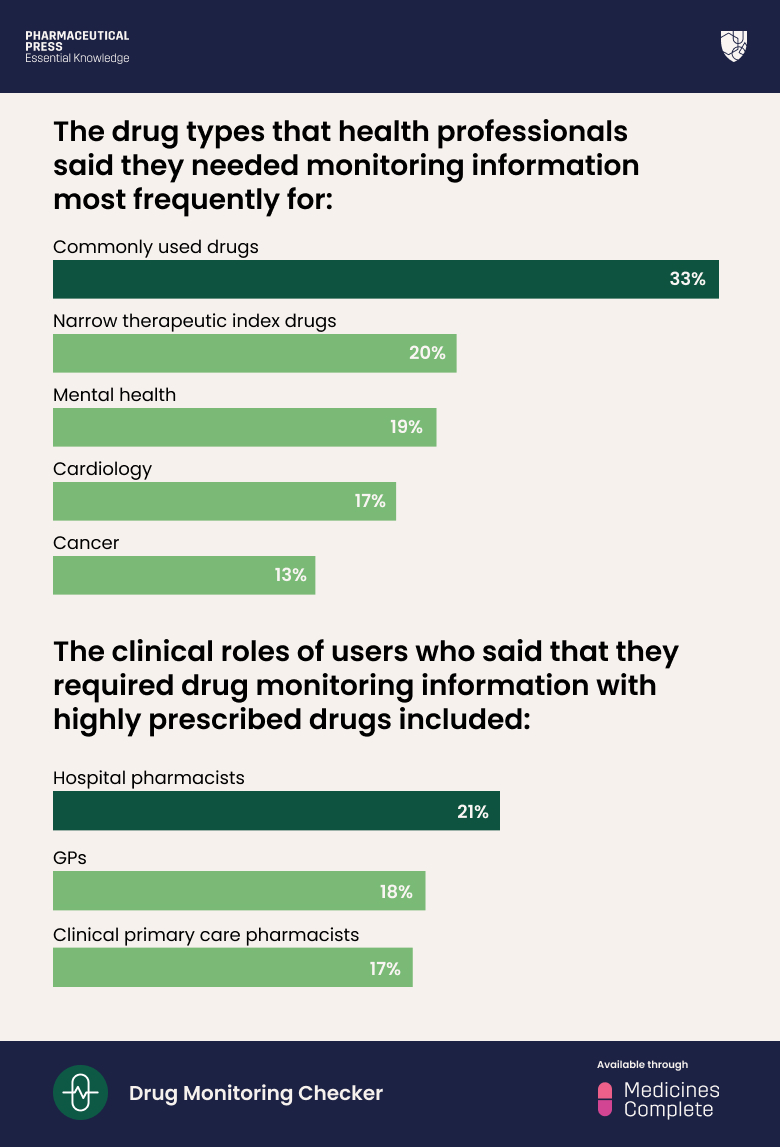

Yet many health professionals report spending a lot of time sourcing and interpreting the information needed to optimise drug therapy. Our May 2020 survey of 500 MedicinesComplete users found that 71% of health professionals searched for drug monitoring information at least once a day.* In another survey of 219 respondents, only 27% said it was “very easy” to find drug monitoring information using currently available resources.

Sourcing accurate information to support drug monitoring can eat into valuable patient-facing time, and slow down the delivery of care.

2.

It’s challenging to navigate drug monitoring guidelines, for example it can be difficult to find a clear rationale for what should be monitored and how often. This is particularly true when information is required for specific indications or special populations, such as children or the elderly. Available guidelines can lack detail, or refer health professionals back to product information, which is often vague and non-specific. A common frustration, for example, is the advice to “monitor regularly”, which is not helpful for health professionals building care plans.

3.

One of the biggest challenges arises at care transitions, or when clinical and prescribing responsibility for a patient moves between care settings. This may be between home, hospital, outpatient, and residential care, for example, or between different healthcare teams or providers. Transitions of care are known to increase the risk of medication errors, as drug therapy is changed, new drugs are added, and doses are altered.⁵

When care is transferred there is a risk of poor communication and unintended changes to medicines, with errors or unintentional changes to medicines occurring in between 30% and 70% of patients.⁵ This may include advice about ongoing monitoring requirements. It is everyone’s responsibility to ensure medicines information is transferred between care teams accurately, and in a timely fashion. However, this isn’t always easy, particularly when patient care follows complex pathways with the involvement of multiple health professionals. Systems and processes often vary between organisations, so sometimes appropriate drug monitoring information can be misplaced or miscommunicated.

*See references

The above survey is reinforced by findings from an audit of UK GPs regarding current testing practices for monitoring long-term conditions. The results revealed that most GPs (78%) spent over 30 minutes per day on testing, yet only half (53%) felt confident in managing abnormal results. In the audit, many expressed uncertainty, citing a lack of evidence and unclear guidelines contributing to increased stress and workload.⁶

Save between five and ten hours a month

In our survey of 219 health professionals in 2020, 28% said the availability of improved drug monitoring resources would save them a substantial amount of time – between five and ten hours a month – and 40% said it would save them one to five hours per month.*

Within the same cohort, 65% of health professionals said more than half of their patients would benefit from them being able to access faster and improved information on drug monitoring.*

Drug Monitoring Checker is an essential tool to support health professionals make effective drug monitoring decisions at the point of care. Speak to our sales team about Drug Monitoring Checker accessible through MedicinesComplete.

Please complete the form below to request a complimentary trial to knowledge products through MedicinesComplete.

References

1. Exploration of reasons for primary care testing (the Why Test study): a UK-wide audit using the Primary care Academic CollaboraTive, British Journal of General Practice, 2024 [https://bjgp.org/content/74/740/e133] accessed 10 April 2025.

2. National Pathology Programme, NHS England, 2014 [https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/pathol-dig-first.pdf] accessed 10 April 2025.

3. Temporal trends in use of tests in UK primary care, 2000-15: retrospective analysis of 250 million tests, BMJ, November 2018 [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30487169/] accessed 10 April 2025.

4. Report of the second phase of the review of pathology services in England Chaired by Lord Carter of Coles: an independent review for the Department of Health, 2008 [https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20130123195523/http:/www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_091985] accessed 10 April 2025.

5. Key priorities for implementation, in Medicines optimisation: the safe and effective use of medicines to enable the best possible outcomes, NICE guideline (NG5), March 2015 [https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng5/chapter/Key-priorities-for-implementation] accessed 17 March 2025.

6. GP’s perspectives on laboratory test use for monitoring long-term conditions: an audit of current testing practice, BMC Family Practice, 2020 [https://bmcprimcare.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12875-020-01331-6] accessed 10 April 2025.

* Our survey, in Drug Monitoring: Three critical challenges faced by health professionals and how to overcome them, downloadable whitepaper, June 2022 [https://www.pharmaceuticalpress.com/resources/whitepaper/drug-monitoring-three-critical-challenges-faced-by-health-professionals-and-how-to-overcome-them/] accessed 26 February 2025.