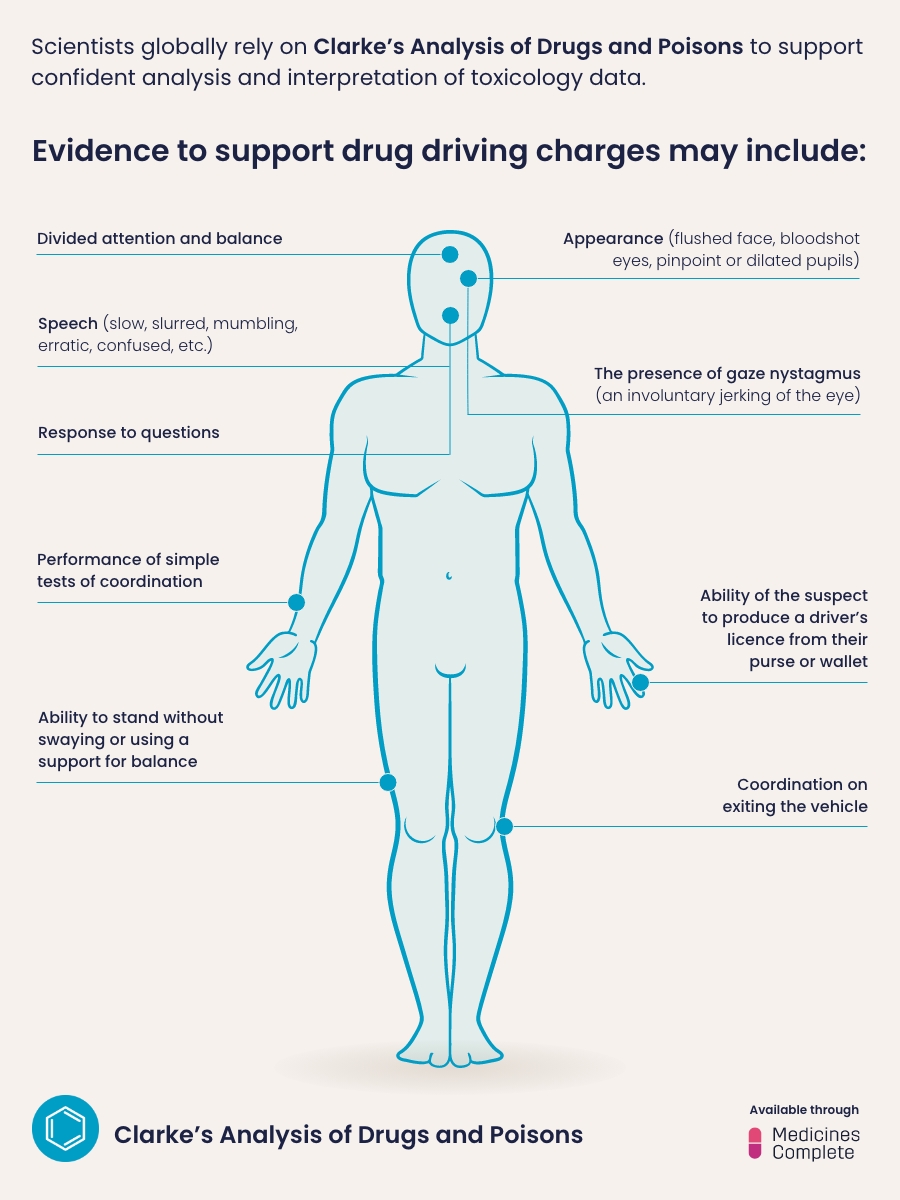

What evidence is used for a drug driving sentence?

Evidence to support drug driving charges may include:

• Appearance (flushed face, bloodshot eyes, pinpoint or dilated pupils)

• Speech (slow, slurred, mumbling, erratic, confused, etc.)

• Response to questions

• Ability of the suspect to produce a driver’s licence from their purse or wallet

• Coordination on exiting the vehicle

• Ability to stand without swaying or using a support for balance

• Performance of simple tests of coordination

• The presence of gaze nystagmus (an involuntary jerking of the eye)

• Divided attention and balance.

All of the above provide cumulative evidence that a subject may be in a state in which the cognitive and psychomotor skills needed for safe driving are to some degree and for some reason deficient. Having established the presence of impairment, the investigation then proceeds to confirming by chemical tests that the reason for the deficit is use of alcohol and/or drugs.

Clarke’s Analysis of Drugs and Poisons aims to be the world’s leading text on the analysis of drugs and poisons. As such, it includes a chapter on driving under the influence of drugs.

Drug driving legislation, enforcement, and prosecution

There are two main approaches to legislating against drivers who drive while under the influence of drugs. The first is an impairment standard, under which a driver is guilty of the crime of DUI or driving while intoxicated/impaired (DWI) if it can be shown that their driving ability is affected by drug or alcohol use.

The second approach is the so-called “per se” legislations, with legal cut-off values for target substances. The rationale for this type of legislation is the difficulty to obtain evidence of reduced fitness and to prove impairment objectively in court. A “per se” legislation makes law enforcement and final prosecution straightforward, certainly for illegal drugs and tends to have a deterrent effect.

For the first approach, the impairment approach, the statutory language used in legislative standards varies widely in different countries and regions. This important variable is often overlooked in the quest to derive thresholds for impairment associated with blood drug concentrations.

There are several barriers to establishing these thresholds. For example, in the USA individual jurisdictions use language such as “impaired to the slightest degree”, “such that the person cannot exercise the same standard of care as a sober person”, “so that the person is less able than the person ordinarily would have been” and so on, which seem to require different standards of evidence. This “affected by” approach is the most straightforward, and relates the person’s behaviour to the crime of impaired driving.

In the USA, indicators of intoxication may be needed legally to provide “probable cause” (a higher standard than reasonable suspicion) to place a subject under arrest in order to allow the collection of a biological sample for testing.

In the UK, a blood specimen can be collected only if a medical practitioner (the forensic medical examiner or FME) is prepared to state that the driver is impaired through the use of drugs. In some European countries and Australian states, biological samples, e.g. OF, can be collected simply by demand of the law-enforcement officer on the basis of erratic driving, signs of recent drug use or a random traffic stop.

The second approach to prosecuting DUID is the so-called “per se approach”. Under this construction, the government, based on its obligation to preserve public health and welfare and in consideration of the risks to its citizens of sharing the roadways with impaired drivers, has moved to outlaw driving after having consumed a drug with potentially intoxicating properties.

This approach is called “per se” if a quantitative standard in blood, oral fluid or urine is set above which driving is prohibited, or as “zero tolerance” if the law defines the offence as having any detectable amount of a proscribed substance present in the body.

In some countries, e.g. Norway, behavioural cut-offs are set, from which is assumed that blood concentrations higher than the established cut-offs will lead to impairment. Generally, these laws apply only to scheduled substances, but would include prescription medications in situations where the subject does not have a legitimate prescription.

Driving and prescription medicines

Having a valid prescription is generally an absolute defence to a “per se” charge, but the individual in most jurisdictions could still be charged under the “affected by” standard, even if they have a prescription, if they show evidence of impairment and/or if the blood concentrations exceed the therapeutic ranges.

The above excerpt is taken from Driving Under the Influence of Drugs (SMR Wille, N Samyn) in Clarke’s Analysis of Drugs and Poisons, available on MedicinesComplete.

Access the full content for more on this topic:

- Signs of impairment

- Drug Legislations and Decision Limits Worldwide

- Laboratory approaches to drug testing in DUID cases.

Discover how MedicinesComplete supports health professionals in confident decision-making at the point of need.