How to calculate drug dosage for special populationsOptimising drug dosage for special populations

Everyone responds differently to medicines, known as inter-individual variation in drug response. Standard dosing regimens in prescribing information, however, are designed for the average adult. They are based on dose–response data derived from observations in many people in clinical trials. It can therefore be difficult for prescribers to predict the clinical response to the use of a specific medicine in any given patient.

The standard dose may not be ideal or safe for all patients, particularly if the drug has not been widely studied in specific patient populations. For people in these special populations the response to the standard dose could either be suboptimal or exaggerated. Tailoring drug therapy with consideration of the drug, disease state, and patient is therefore important to ensure efficacy and minimise harm. Factors such as age, pregnancy, and organ dysfunction can all affect drug response.

Apply for a trial of MedicinesComplete to calculate drug dosage and prevent patient harm. Just enter “drug dosage” into the further details section of the form below.

Optimising drug dosage, then, is a critical element of providing safe, effective, personalised care. In this article, we look at some of the key factors that influence drug dosing in special populations, and explain how health professionals can easily access the information they need to ensure the most appropriate dose is prescribed.

Drug dosage

How a person responds to a drug depends on a range of factors, including the drug’s pharmacokinetics (PK), (i.e. what the body does to the drug) pharmacodynamics (PD) (i.e. how the medicine acts within the body). It is also now clear that an individual’s response to a drug may also be influenced by their genetic makeup, known as pharmacogenomics.

When a medicine is licensed it is granted a marketing authorisation and the prescribing information (Summary of Product Characteristics) includes information on the standard dose. This is based on evidence from clinical trials, yet studies have strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, meaning that most drugs are primarily studied in so-called “average” populations and information on their use in the special populations below may be very limited.

The prescribing information has a standard format which includes information, where available, on the dose in these special populations:

• paediatric and elderly

• patients with kidney or liver impairment

• patients who are pregnant or breastfeeding

• patients with a particular genotype.

Older people, children, pregnant women, people with kidney or liver dysfunction, for example, or people receiving critical or palliative care will therefore often present unique challenges for the prescriber when choosing the optimal dose of a medicine. There may be significant physiological differences that impact how drugs are absorbed, metabolised, distributed, and excreted. Depending on the individual, the standard dose could either be too high, resulting in adverse events or toxicity, or sub-optimal, reducing the agent’s therapeutic effect.

General principles

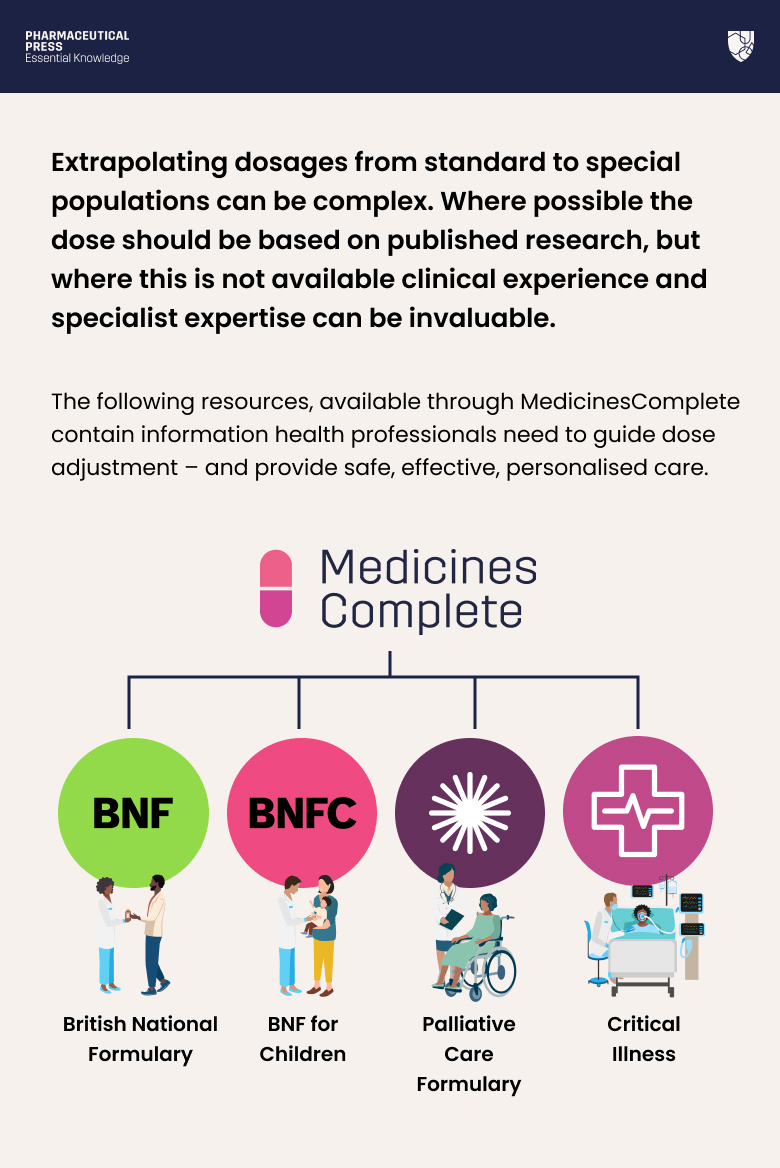

Extrapolating dosages from standard to special populations can be complex. Where possible the dose should be based on published research, but where this is not available clinical experience and specialist expertise can be invaluable.

British National Formulary (BNF), BNF for Children (BNFC), Critical Illness, and Palliative Care Formulary contain information health professionals need to guide dose adjustment – and provide safe, effective, personalised care.

In many situations it is important to monitor key parameters during treatment, such as hepatic or renal function, or serum drug concentrations, and adjust the dose accordingly. This can help balance benefits and risks in order to optimise therapeutic outcomes.

Practical and evidence based, British National Formulary (BNF) is the only drug formulary in the world that is both independent, and has rigorous, accredited content creation processes. Find out more.

Paediatrics

Children, and particularly neonates, differ from adults in their response to drugs. A drug’s pharmacokinetics can be very different in children. For example, reduced gastric acid secretion and relatively short bowel length can influence drug bioavailability.¹

Paediatric doses are usually extrapolated from adult doses, based on bodyweight or body surface area (BSA), or presented for specific age ranges.¹ Occasionally young children may require a higher dose than adults because of their higher metabolic rates. Drug monographs in BNFC give detailed prescribing information for age ranges in neonates and children. Doses of dalteparin sodium for the treatment of venous or arterial thromboembolism, for example, are provided for four age ranges:

- neonate (0 to 28 days)

- one to 23 months

- 2 to 7 seven years

- 8 to 17 years.²

Pregnancy

During pregnancy, drugs can have harmful effects on the embryo or foetus, and evidence on the safety of many medicines for women who are pregnant or with childbearing potential is lacking. Yet in some cases, drug treatment is appropriate as the risks of not treating the patient will outweigh the risks of prescribing.³

When treating or advising pregnant women, health professionals can consult the relevant drug monograph in BNF or BNFC, where any concerns and contraindications will be listed. According to BNF, drugs which have been extensively used during pregnancy and appear to be safe should be prescribed in preference to new or untried drugs. It also recommends health professionals use the lowest effective dose.⁴

Organ dysfunction

Liver disease can alter the response to drugs in several ways and hepatic metabolism is the main route of elimination for most drugs. When liver disease is severe, this can impede metabolism, increasing the risk of drug accumulation and toxicity.⁵

Phenytoin, for example, carries an increased risk of accumulation and toxicity in hepatic impairment, due to decreased protein binding, hypoalbuminaemia, or hyperbilirubinaemia. The BNF monograph cites manufacturer recommendations to reduce the dose in these patients.⁶ Where caution is necessary when prescribing a medicine for patients with hepatic impairment, this will be stated in the BNF monograph.⁵

In addition, renal impairment can reduce the excretion of a drug or its metabolites, leading to toxicity. In acute kidney injury (AKI) and chronic kidney disease, medicines that are eliminated via the kidneys can accumulate, contributing to further renal impairment or adverse effects.⁷

Again, advice will be included in the drug’s BNF monograph if caution is necessary. The entry for metformin hydrochloride, for example, contains a section on renal impairment. It recommends the dose be reduced in people with moderate impairment, and the drug be avoided if estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGRF) is <30 mL/minute/1.73 m².⁸

MedicinesComplete makes it easy for health professionals to access trusted evidence-based guidance and medicines information to support confident decision making at the point of need. Request a complimentary trial.

Elderly patients

Prescribing an appropriate dose is vitally important in elderly patients. Enhanced sensitivity of the central nervous system, as well as pharmacokinetic changes, such as reduced renal clearance and liver volume, can affect how older people respond to medicines.⁹ These factors significantly increase the risk of drug toxicity.

BNF highlights that dosage in the elderly should generally be “substantially lower” than in younger patients. It is common to start with about 50% of the adult dose.⁹ Some drugs, however, should be avoided altogether. The BNF monograph for nicardipine, for example, advises that it is potentially inappropriate for elderly people due to the risk of syncope and falls.¹⁰ BNF monographs may include specific guidance on dosing in the elderly and will also highlight any age-specific considerations in the “Cautions” section.

Intensive care unit (ICU) and palliative care patients

Critical illness can alter the PK profile of many medicines commonly prescribed in ICU and other settings. Doses need to be adjusted according to these changes, as well as any AKI, renal replacement therapy, or other extracorporeal treatments.¹¹ There is a risk that insufficient doses are given; for example standard doses of beta-lactam antibiotics in critically ill patients can result in low serum concentrations with poor outcomes.

Critical Illness contains detailed information on dose adjustment in critically ill patients. The ciprofloxacin monograph, for example, recommends health professionals consider dose adjustments for individuals with AKI, with specific guidance based on whether they have a stage 1, stage 2, or stage 3 diagnosis.¹²

In palliative care, primary disease progression, polypharmacy, and organ failure, including hepatic and liver dysfunction, are among the factors that put people at an increased risk of adverse and toxic drug effects.¹³ ¹⁴ Palliative Care Formulary contains rigorously researched information grounded in clinical practice tailored for use in palliative and hospice care settings. This trusted source goes beyond standard references, providing health professionals with in-depth, practical guidance on drugs and treatment regimens to help improve quality of life.

Dosing, then, is a complex process with personalised medicine at its core. Health professionals need to consider a range of factors including liver and kidney function and concomitant medications. These factors are set out in Palliative Care Formulary, which explains how gabapentin dosing, for example, should be adjusted according to kidney function.¹⁵

Pharmacogenomics

Pharmacogenomics is an emerging field that studies how genes affect a person’s response to medicines. Genetic alterations or ‘polymorphisms’ can affect PK or PD and cause variations in drug response. For some medicines, genotyping is now used to determine the dose that is given or whether the drug can be safely given at all. For example, eliglustat is a treatment option for Gaucher disease. Before initiation of treatment, patients must be genotyped to determine the CYP2D6 metaboliser status. The dose prescribed is then dependent on whether the patient is a poor, intermediate, or extensive metaboliser.¹⁶

Patient-centred personalised care

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to medicines dosing. Some special populations require careful consideration with regard to calculating, adjusting and monitoring the dose. Yet whatever the reason for dose adjustment, it is essential to communicate the rationale clearly with patients and their families. This will help them to understand the importance of taking the correct dose at the correct time, and of the need to report any deterioration or possible adverse events in a timely manner.

By understanding these critical elements, health professionals can better navigate the complexities of dosing in special populations, making sure the right drug reaches the right patient at the right dose – improving care and boosting the chances of treatment success.

Please complete the form below to request a complimentary trial to knowledge products through MedicinesComplete.

References

1. Fernandez, E., Perez, R., et al. (2011). Factors and mechanisms for pharmacokinetic differences between pediatric population and adults. Pharmaceutics, 3(1), 53-72.

2. BNFC. (2024). Dalteparin sodium. Available at: https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/bnfc/_694891763?hspl=Dalteparin%20sodium Last accessed: 13th January 2025.

3. Abduljalil, K., Badhan, R. K. S. (2020). Drug dosing during pregnancy—opportunities for physiologically based pharmacokinetic models. Journal of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, 47(4), 319-340.

4. BNF. (2022). Prescribing in pregnancy. Available at: https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/bnf/PHP97241?hspl=prescribing&hspl=in&hspl=pregnancy Last accessed: 13th January 2025.

5. BNF. (2024). Prescribing in hepatic impairment. Available at: https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/bnf/PHP97233?hspl=prescribing&hspl=in&hspl=hepatic&hspl=impairment Last accessed: 13th January 2025.

6. BNF. (2022). Phenytoin. Available at: https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/bnf/_789756225?hspl=Phenytoin Last accessed: 13th January 2025.

7. BNF. (2024). Prescribing in renal impairment. Available at: https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/bnf/PHP97238?hspl=prescribing&hspl=in&hspl=renal&hspl=impairment Last accessed: 13th January 2025.

8. BNF. (2024). Metformin hydrochloride. Available at: https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/bnf/_884485368?hspl=Metformin%20hydrochloride Last accessed: 13th January 2025.

9. BNF. (2024). Prescribing in the elderly. Available at: https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/bnf/PHP98618?hspl=prescribing&hspl=for&hspl=the&hspl=elderly Last accessed: 13th January 2025.

10. BNF. (2024). Nicardipine hydrochloride. Available at: https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/bnf/_842357058?hspl=nicardipine%20hydrochloride Last accessed: 13th January 2025.

11. Critical Illness. (2024). About critical illness. Available at: https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/critical/98?hspl=considerations Last accessed: 13th January 2025.

12. Critical Illness. (2024). Ciprofloxacin. Available at https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/critical/103?hspl=Ciprofloxacin Last accessed: 13th January 2025.

13. Zaporowska-Stachowiak, I., Stachowiak-Szymczak, K., et al. (2020). Haloperidol in palliative care: indications and risks. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 132, 110772.

14.Masman, A. D., van Dijk, M., et al. (2015). Medication use during end-of-life care in a palliative care centre. International journal of clinical pharmacy, 37, 767-775.

15. Palliative Care Formulary. (2024). Gabapentin and pregabalin. Available at: https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/palliative/gabapentin-and-pregabalin?hspl=dose&hspl=adjustment#content%2Fpalliative%2Fgabapentin-and-pregabalin%23dose-and-use Last accessed: 13th January 2024.

16. BNF (2024) Eliglustat https://www-medicinescomplete-com.knowledge.idm.oclc.org/#/content/bnf/_948822397#content%2Fbnf%2F_948822397%2 Last accessed 28th January 2025.