Common mental health medicationsMental health medications

The use of medication for the treatment of mental health conditions can be a divisive subject among health professionals, as some believe they can do more harm than good.

Everyone has ‘mental health’, just as everyone has ‘physical health’.¹ Physical health conditions, such as heart disease and diabetes, are often influenced by genetics and lifestyle. Mental health conditions can be due to various factors, including genetics, trauma, life events or substance misuse.² Mental and physical health are inextricably linked. Chronic health conditions can affect mental health, for example, by causing depression or anxiety.

Mental health medication list:

The above common mental health medications list includes: antidepressants, anti-anxiety medications or anxiolytics, stimulant medications, antipsychotics, and antimanic drugs. Smoking cessation drugs may also be involved.

Please complete the form at the bottom of this article to request a complimentary trial of MedicinesComplete.

While medication can be beneficial to treat or prevent the symptoms of most mental illnesses, it may not be the first-line approach. Specialist health professionals tend to recommend that medicines are taken as part of a more comprehensive treatment plan.³ The use of medicines depends on the diagnosis, the severity of symptoms i.e. their impact on the person’s quality of life, and the suitability of other therapies.⁴

In this article, we will explore the use of medication in the treatment of mental health conditions, providing valuable insights for health professionals considering the impact of drug therapy in mental health care.

What is mental health?

Mental health exists on a continuum, with mental health and mental illness at the two extreme ends. According to NHS England, one in four adults experiences issues with their mental health in any given year⁵ and the most recent data suggest one in five children aged 8 to 16 years has a probable mental disorder.⁶ Mental health refers to a person’s emotional, psychological and social wellbeing, and this can impact every area of their life, from how they think, feel and behave, to their ability to cope with stress, form relationships and make good decisions.⁷

A person with poor mental health, or who has a mental health condition, may find their ability to do any of these things – and to live a fulfilling life – compromised. However, mental health is a complex issue and, since every person is unique, what constitutes mental ‘health’ can vary greatly between individuals.⁸

What determines mental health?

Mental health, or the risk of mental health issues, can be impacted by exposure to unfavourable social, economic, geopolitical, and environmental circumstances.⁸ These include poverty, violence, inequality, and social deprivation. For example, there is evidence of an association between trauma or mistreatment in childhood and a range of psychiatric conditions, including depression, anxiety and psychosis.⁹ People who are socially or economically disadvantaged are at much higher risk of developing mental health conditions.¹⁰ There is evidence of a direct correlation between poverty and mental health problems.¹⁰ This is not just a one-way effect; poverty is both a cause of mental illness and a consequence.¹⁰ ¹¹

There is now a better understanding of the genetic contribution to mental health. Some conditions are likely to have a genetic component, such as autism, bipolar disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and schizophrenia.¹² ¹³ There is no single genetic switch that when flipped causes a mental disorder, however, but a combination of multiple genetic and environmental factors are involved.

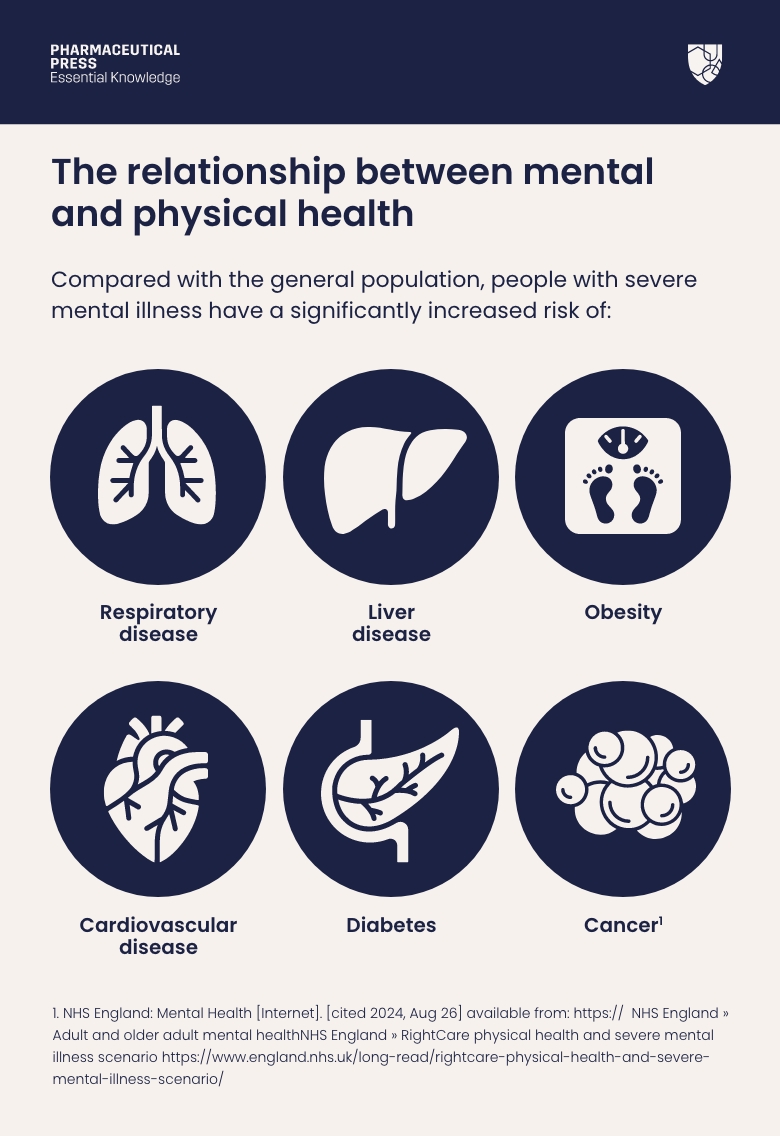

The relationship between mental and physical health

Mental and physical health are directly correlated. Statistics show that adults living with a severe mental illness are almost five times more likely to die prematurely than those without such conditions.⁵

Smoking is the largest cause of preventable death in England.¹⁴ People with poor mental health die on average 10-20 years earlier than the general population, and smoking is the biggest cause of this life expectancy gap.¹⁵ Two thirds of these deaths are from avoidable physical illnesses, including heart disease and cancer.

Compared with the general population, people with severe mental illness have a significantly increased risk of:⁵

– respiratory disease

– liver disease

– obesity

– cardiovascular disease

– diabetes

– cancer

Regular physical health checks and psychosocial support could help improve wellbeing and mitigate the risk of these comorbidities.

Download our Psychotropic Drug Directory user guide.

Exploring the role of medication in mental health treatment

Mental health is a multi-faceted issue. While many mental health conditions can’t be cured, most can be treated effectively to significantly improve symptoms and to enable a person to function at home, work, school, and in social environments. People with mental illnesses can recover and live productive and healthy lives. Treatment can take many forms, with medication playing a role alongside other therapies such as talking therapies (e.g. cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)), self-help (e.g. lifestyle changes, guided self-help or physical activity) and alternative therapies (e.g. mindfulness or acupuncture).

Types of medication for mental health conditions

A wide range of medicines is used to treat mental illnesses. As with any drug, the choice of therapy will depend on the condition a person has, their clinical needs and preference, and should follow evidence-based guidance. As with all drugs, there is a risk of side effects and patients should be counselled about which they might expect and when to seek advice from a health professional. The response to treatment needs to be monitored carefully with all of these medicines.

We list the main categories of medicines used for mental health conditions.

The main categories of medicines used for mental health conditions are:

- Antidepressants

Primarily prescribed for depression, but also sometimes helpful for other conditions including anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder, and pain, antidepressants are used to improve mood and quality of life, and to reduce the risk of relapse or recurrence.¹⁶ They generally take up to four weeks to start working, when they can improve sleep, energy levels, appetite and concentration, as well as having a positive effect on mood. There are several types of antidepressant (including tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and monoamine oxidase inhibitors). As well as needing time to take effect, the dose may need to be adjusted and it may be necessary to try several medicines to find one that works well for an individual patient.¹⁶ Response to treatment also needs to be monitored regularly.

It’s important to be aware that some young people (under 25 years of age) prescribed antidepressants may experience an increase in self-harming/suicidal thoughts and harmful behaviours. This often happens soon after first starting the drug or when the dosage is increased. For this reason, it’s advised that young people taking antidepressants are closely monitored by their caregivers and have a risk management strategy in place.¹⁶ Some antidepressants should not be used at all in children and adolescents and some may only be used for moderate to severe depression.

People taking antidepressant medication need to be advised that they should not stop the treatment abruptly because there can be withdrawal symptoms. Instead, the dose is generally reduced in stages over time, called ‘tapering’.¹⁶

- Anti-anxiety medications or anxiolytics

Research by the Mental Health Foundation in 2023 showed that nearly 60% of UK adults surveyed reported anxiety that interfered in their daily lives during the previous two weeks.¹⁷ Self-help strategies (e.g. breathing techniques, applied relaxation) and talking therapies such as CBT are first-line approaches to manage anxiety.¹⁷ The medication mainly prescribed, if required, is antidepressants, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. These can help reduce symptoms, such as feeling tense, sweating, trouble concentrating and panic attacks.¹⁸ Beta-adrenoceptor blockers can also be used for symptoms such as palpitation and tremor. Benzodiazepines such as diazepam are indicated only for the short-term relief of anxiety; long-term use should be avoided.¹⁹

- Stimulant medications

Stimulant medications are typically prescribed to treat ADHD, and they work by increasing alertness, attention and energy levels.³ They also improve these cognitive functions irrespective of a diagnosis.³ A diagnosis of ADHD, either in adults or children, should be made by specialist health professionals with training and expertise in the diagnosis of ADHD.¹⁹ Several stimulants are available, examples include dexamfetamine and lisdexamfetamine. Some of these need to be taken daily, while some can be taken just on the days where the benefits are particularly needed – for example, some children may take the medication only on school days.²⁰ ²²

Small doses of modified-release preparations are usually prescribed to begin with, and the dose carefully titrated, so that the patient’s response can be carefully monitored.²¹ Non-stimulant medicines, such as atomoxetine, may also be prescribed for ADHD.

- Antipsychotics

Antipsychotics, also known as neuroleptics, are mainly used to treat disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and psychotic depression.³ The aim of treatment is to reduce acute symptoms and allow the patient to function more normally. A large number of antipsychotics is available, generally divided into two classes, known as first- and second-generation drugs. Examples of first-generation antipsychotics are chlorpromazine and haloperidol. Second-generation drugs include clozapine and risperidone. In the USA, the Food and Drug Administration requires that all antipsychotics include a black box warning about the increased rates of stroke and death in older adults with dementia.³ In the UK this risk is covered in prescribing information for individual medicines. First-generation antipsychotics are more likely to cause certain side effects, such as extrapyramidal (movement) disorders. The newer, second-generation drugs have several other important adverse effects, such as weight gain and glucose intolerance.²³ Antipsychotics can take several days or weeks to reduce psychotic symptoms, such as hallucinations or delusional thoughts.²⁴

- Antimanic drugs

Antimanic drugs (or mood stabilisers) are typically used to treat bipolar disorder to manage acute episodes of mania or hypomania and to prevent recurrence.³ ²⁵ Lithium is an effective mood stabiliser and can be used for both acute episodes or long-term management, where it can reduce the risk of suicidal behaviour.²⁶ Mood stabilisers may be prescribed alongside antidepressants in a type of bipolar disorder known as rapid cycling, when a person has four or more episodes of mania, hypomania or depression within a year.²⁶ ²⁷ Antipsychotic drugs can also be used in the treatment of mania or hypomania.

- Smoking cessation drugs

As we know, people with a mental health condition are more likely to smoke and as a result, have a much lower life expectancy.¹⁵ Encouraging patients with mental illness to quit smoking benefits their overall health outcomes.¹⁵ In addition to Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT), other medicines that can help people to stop include varenicline and bupropion.²⁸ These are usually prescribed in conjunction with behavioural support and counselling.²⁸

- Managing side effects

All medicines have side effects, and those used for mental health conditions are no exception. Side effects and risks vary depending on the drug, dose and of course the patient. For certain medications, the dose is incrementally increased (known as titration) to minimise potential side effects and enable close monitoring by health professionals. This gradual dose escalation approach helps optimise treatment response and patient safety.

- Emergency mental health medications for times of crisis

As we know, mental health occurs on a spectrum and can rapidly improve or decline based on an individual’s circumstances. In times of crisis, mental health can quickly plummet, and urgent intervention may be necessary to avoid a situation which may result in harm to the individual or others. Exactly what constitutes a crisis is subjective and depends on the unique circumstances. Health professionals may need to administer medication to achieve a rapid improvement in the patient’s condition. For example, antipsychotic medications may be given, often by intramuscular injection, to a patient who is extremely agitated, violent or psychotic in a psychiatric emergency.²⁹ ³⁰

Importance of medication adherence for effective management

Adhering to (or compliance with) the recommendations on how to take all these medicines is essential if they are to work successfully and with minimal side effects.³¹

Taking medicines regularly as prescribed can help stabilise symptoms, prevent relapse and improve overall wellbeing. If doses are missed, however, symptoms can worsen and decrease the patient’s quality of life. Patients should be encouraged to follow the regimen as closely as possible, and to speak to a health professional about any challenges or concerns.

Psychotropic Drug Directory supports the optimal and rational use of mental health medications, to improve the quality of life for people with mental health needs. Find out more.

In conclusion, medication plays a vital role in the treatment of mental health conditions. It is essential that health professionals carefully consider the benefits, potential side effects and the individual patient’s characteristics when choosing to prescribe drugs for these conditions. The choice to use medication should always be a shared decision, with both the patient and the health professional being aware of how the response to treatment will be monitored as necessary, to minimise side effects and optimise patient outcomes.

Trial form

Please complete the form below to request a complimentary trial to knowledge products through MedicinesComplete.

References

1. Mental Health Foundation | Everyone deserves good mental health https://mentalhealth.org.uk Accessed 4 September 2024

2. What causes mental health problems? – Mind

3. National Institute of Mental Health: Mental Health Medications [Internet]. [cited 2024, Aug 26] available from: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/mental-health-medications

4. About psychiatric medication – Mind

5. NHS England: Mental Health [Internet]. [cited 2024, Aug 26] available from: https:// NHS England » Adult and older adult mental healthNHS England » RightCare physical health and severe mental illness scenario https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/rightcare-physical-health-and-severe-mental-illness-scenario/

6. NHS England. Mental health of children and young people in England, 2023 – wave 4 follow up to the 2017 survey. Part 1: Mental health – NHS England Digital

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: About Mental Health [Internet]. [cited 2024, Aug 26] available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/learn/index.htm

8. World Health Organization: Mental Health [Internet]. [cited 2024, Aug 26] available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response

9. Baldwin, Jessie R., et al. ‘Childhood Maltreatment and Mental Health Problems: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Quasi-Experimental Studies’. The American Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 180, no. 2, Feb. 2023, pp. 117–26. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.20220174

10. Mind: Understanding the MH needs of people living in poverty https://www.mind.org.uk/about-us/our-strategy/working-harder-for people-facing-poverty/ facts-and-figures-about-poverty-and-mental-health/

11. Knifton, Lee, and Greig Inglis. ‘Poverty and Mental Health: Policy, Practice and Research Implications’. BJPsych Bulletin, vol. 44, no. 5, pp. 193–96. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2020.78. Accessed 26 Aug. 2024

12. National Institutes of, and Biological Sciences Curriculum Study. ‘Information about Mental Illness and the Brain’. NIH Curriculum Supplement Series [Internet], National Institutes of Health (US), 2007. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK20369/

13. Genes and Mental Illness — Department of Psychiatry (ox.ac.uk) https://www.psych.ox.ac.uk/news/genes-and-mental-illness

14. House of Commons Library: Statistics on Smoking [Internet]. [cited 2024, Aug 27] available from: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-7648/

15. Royal College of Physicians: Primary Care Guidance on Smoking and Mental Health Disorders [Internet]. [cited 2024, Aug 27] available from: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/improving-care/better-mh-policy/policy/primary-care-guidance-on-smoking-and-mental-disorders-2014-update.pdf?sfvrsn=5824ccd5_2

16. NICE guideline [NG222] Depression in adults: treatment and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence June 2022.

17. Mental Health Foundation: Uncertain times; Anxiety in the UK and how to tackle it [Internet]. [cited 2024, Aug 27] available from: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/our-work/public-engagement/mental-health-awareness-week/anxiety-report

18. World Health Organization: Anxiety Disorders [Internet]. [cited 2024, Aug 27] available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/anxiety-disorders

19. BNF Hypnotics and anxiolytics | Treatment summaries | BNF | NICE

20. NICE Guideline [NG87] Recommendations | Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and management | Guidance | NICE

21. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | Treatment summaries | BNF | NICE

22. NHS: Treatment Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [Internet]. [cited 2024, Aug 27] available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-adhd/treatment/

23. Psychoses and related disorders | Treatment summaries | BNF | NICE

24. Overview – Psychosis – NHS (www.nhs.uk)

25. Tondo, Leonardo, and Ross J. Baldessarini. ‘Prevention of Suicidal Behavior with Lithium Treatment in Patients with Recurrent Mood Disorders’. International Journal of Bipolar Disorders, vol. 12, Mar. 2024, p. 6. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40345-024-00326-x

26. Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance: Rapid Cycling [Internet]. [cited 2024, Aug 27] available from: https://www.dbsalliance.org/education/bipolar-disorder/rapid-cycling-bipolar/

27. Mania and hypomania | Treatment summaries | BNF | NICE

28. NICE guideline [NG209] Tobacco: preventing uptake, promoting quitting and treating dependence. Recommendations on treating tobacco dependence | Tobacco: preventing uptake, promoting quitting and treating dependence | Guidance | NICE Accessed 3 Sept 2024.

29. How antipsychotics can help – Mind

30. Extein, Irl. ‘Psychopharmacology in Psychiatric Emergencies’. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, vol. 10, no. 3, Sept. 1981, pp. 189–204. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.2190/83PE-KC25-5BE7-8LWJ

31. National Alliance on Mental Illness: Medication Plan Adherence [Internet]. [cited Aug 27] available from: https://www.nami.org/about-mental-illness/treatments/mental-health-medications/medication-plan-adherence/#